Advice for working with Policing Consultants

Advice for working with Policing Consultants

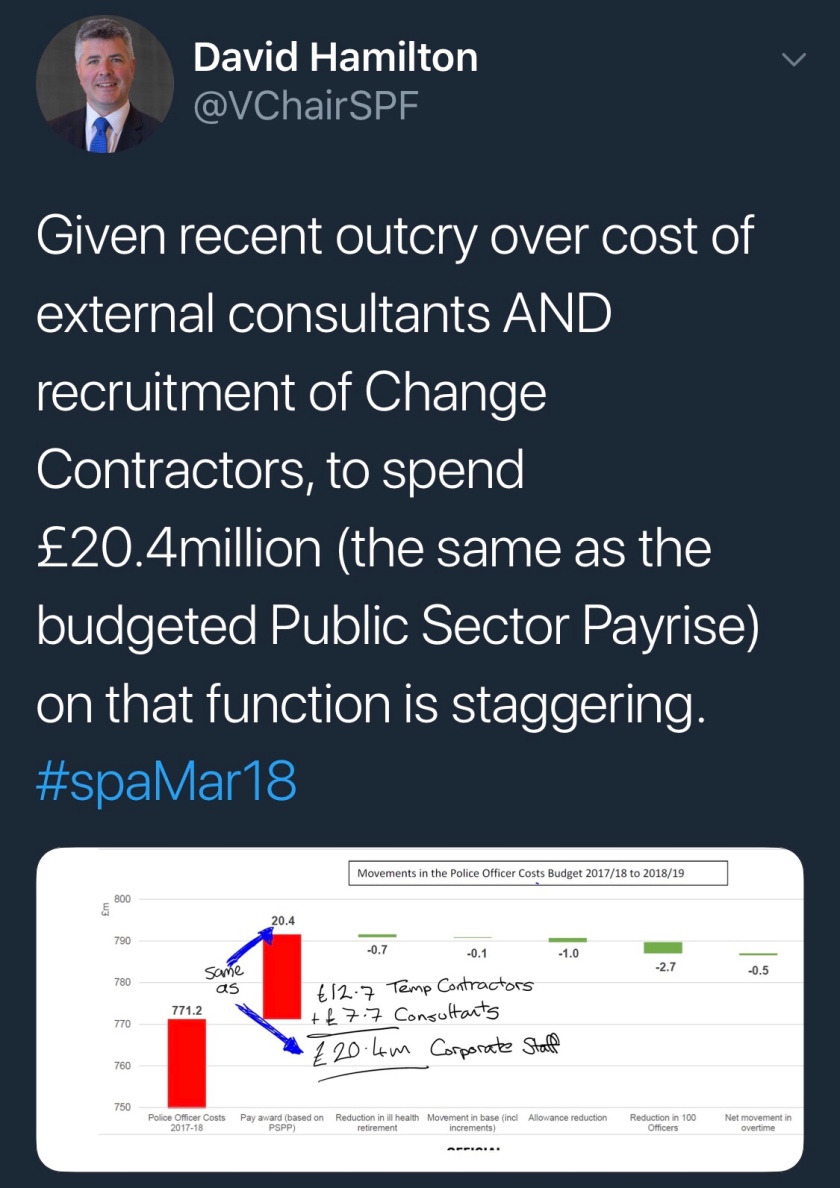

Police forces in the UK spend a lot of money on consultants, a LOT of money. For better or worse over the years I have worked with many on a number of short & longer term policing projects.

I’ll also confess up front to being one for a period of time before I joined the job, albeit in a related industry, so I feel I have a decent sense of where they come from.

I appreciate the following will come across as perhaps a little cynical at times but it is drawn from lessons I have learned. I hasten to add as well it’s nothing personal as most of the consultants I have worked with are lovely folk, though clueless about policing in many instances.

Modus Operandi

Let’s cover a few key areas to be aware of with regards to how your consultants may work:

• If they have worked a similar policing consultancy elsewhere you can expect them to discretely template the work. Remember for many this is the only actual policing exposure & experience they have.

• They will trawl your own organisational files & you will see them pulling together half developed ideas previously considered but not implemented in your own force area. They may take advantage of a force’s previous timidity in program change and risk.

• They will seek to work with project leads rather than those actually working the product.

• They will undertake a lot of ‘development work’ which does not necessarily contribute directly to you producing desired outcomes.

• They favour style over substance. Their docs will often look pretty & be full of buzz word-like concepts with little depth underneath.

• They will look to up-sell. They know the contact limit of liability as well as what they signed on for initially. They may look to generate more revenue from within the limit of liability by ‘bringing in’ additional ‘experts’ as well as running ‘workshops’ at additional cost.

Advice & Tips

So given the above can I offer the following tips as to how to work with them:

• First, ask yourself what you need them for. Before deciding on a consultant solution you should ensure you exhaust internal consultancy options. Cops come from all walks of life. Chances are you already have folk with many of these skill sets in your force who you can call on to get the outcomes you desire. They’ll do it faster, cheaper and are already in tune with the force.

• To do this however you need to look past rank and acknowledge the skill set. That constable that was in marketing for 10 years before they joined the job 2 years ago? Yeah, they know more about it than you…..

• Ask yourself also how committed is the force to this change? You’re about to spend a lot of money. You should be sure that there will be value for this money and that the product isn’t going to sit in a drawer.

• If you do decide on a Consultancy look for one that focuses on what you specifically need. All to often we provide large contracts to large firms based off a 50 page (template) tender document. Smaller, more specialised consultants can often be more suitable and more cost effective to boot. Look to place your contract with the leaner, hungrier Consultancy.

• Also, look further than their record of previous policing projects. Did the project they work on actually achieve what they are claiming? Compare their tender document to their previous work. Are they really putting together a bespoke offer or just dressing up previous projects?

• Keep the contract tight and specific to where you want them placed and the key expertise you require. This seems to go without saying but we see generic, large Consultancy teams offered to police that whilst look great on paper often spend a lot of time needing to get up to speed on organisational need and containing a number of junior, intelligent young men and women with no basis in the realities of policing.

• Once the contract is let ensure the consultants are working with the team members actually producing content and product. Don’t let them cosset up to the senior team leaders. If they do this they just become ‘reviewers’ of the work your staff are already doing rather than contributing at the coal face.

• Alongside this, avoid formalised back-briefs and presentations to project sponsors. These invariably involve shiny PowerPoint presentations overseen by the consultants which result in project sponsors failing to get to grips with the detail. This creates confusion and delay. If you look up and more of your team are working on PowerPoints than product you’re doing it wrong.

• If you are a project sponsor, insist on sitting down with the staff doing the work and engage yourself in depth. Nice back-briefs with pretty slides are a poor substitute and detract from the time your team is actually working the problem. If it’s important enough for you to commission it’s important enough to get your hands dirty.

• Be pragmatic. Change projects are a hard slog. Constantly ask yourself what the key themes and phrases being offered by the consultants really mean in practical terms. Ask also if what is being proposed is genuinely feasible in the timeframes allotted. What does success, in pragmatic terms, look like. This is probably one area I would perhaps go against own instincts and suggest being conservative with regards to what can be achieved. Plenty of serious improvements can come from numerous marginal gains.

I don’t need to tell you how tight money is at the moment in policing. Consultancies can be a useful, short term filler for gaps in an organisation, but they can also become an organisational sea-anchor if not tightly framed, managed and held to account.

You’ll waste a lot of time and money if you let them drive the project rather than drive them to produce the outcomes they are contracted to.